Bawsey (‘Baew’s Island’, Norfolk. Image from https://waternames.wordpress.com/images-of-watery-places/

This article first appeared in Landscape Architecture Magazine in August 2017.

One of the joys of travel, even of armchair travel, is the discovery of euphonious place names. I’ve driven through both Humptulips, on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, and Quonochontaug, in Rhode Island. Both of these are names that flow off the tongue (well, with a little practice). This is an apt metaphor, given that both names describe the flow and flood—the hydrological characteristics of each site. Humptulips, in the tongue of the Chehalis Tribe, tells that it is “hard to pole” a canoe through the river, which follows a convoluted course that includes fast, narrow torrents, and Quonochontaug (Narragansett for “at the long pond”) is along a string of broad, placid coastal lagoons.

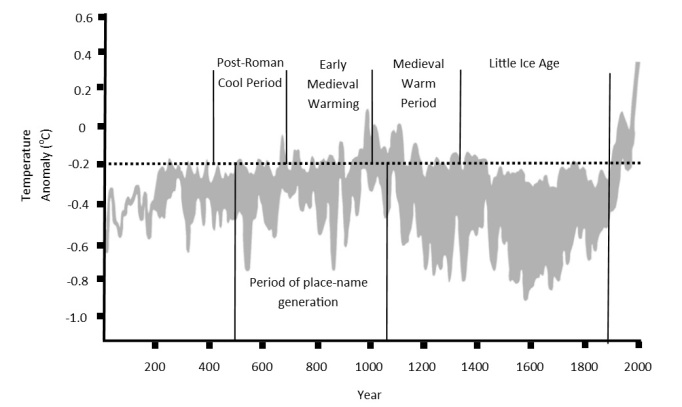

The guide that Indigenous names can provide to landscape qualities and to human interactions with landscape may be followed anywhere such names have not been erased by the conquest of colonialism. This is no less true in Britain, where four British universities, Leicester, Southampton, Nottingham, and Wales have joined forces under a grant from the Leverhulme trust for a two-year study of place names called ‘Flood and Flow’. In Britain, an extra dimension to the record of place names provides a set of clues to how particular landscapes might respond to global warming in the near future. In the period between 700 and 1000 AD, temperatures in the British Isles rose rapidly after a cold phase that began in 400 AD. Extreme weather and an abundance of precipitation in this time is a historic parallel to our present-day situation, and thus the Anglo-Saxon names have once again become meaningfully descriptive of their sites.

Not only is this helpful, but a great many of Britain’s present place names were devised in precisely this period. So, though few written records remain from this time, even a modern map holds a hydrographic key to possible futures that have been written in the past.

Some of these names have particular poignancy: Muchelney, in the Somerset Levels, was cut off during the extreme winter floods in 2013-14. Muchelney means ‘big island’. Communities along the River Swale in Yorkshire have increasingly frequent opportunities to find out that its name derives from Old English swalwe, meaning ‘gush of water’. The River Trent is “the trespasser”.

Dr. Richard Jones at the University of Leicester is Flood and Flow’s Principal Investigator and a specialist in medieval landscapes. He explains how the project’s aims fit within a larger understanding of indigenous naming: “Place-names are used by all Indigenous, aboriginal and First Nations peoples to communicate information about the local presence, behaviour and characteristics of water. For these communities, such names helped them to share and pass on the Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) gained through generations of observation of the flood and flow of water through their home grounds. As such, such names act as active makers of place rather than the passive markers of space they have become in the modern western mind.” TEK describes much of how we have come to understand landscape in recent years, as both maker of people and made by people.

Jones says, speaking of the project’s potential, “It is exciting to ponder how many possibilities might exist everywhere in the world to apply this knowledge—TEK—and to build a richer picture of both the lived and designed landscape from the poetry of original place names.”

For the Flood and Flow website see https://waternames.wordpress.com/, and for an in-depth analysis, see Dr. Richard Jones’s paper “Responding to Modern Flooding: Old English Place-Names as a Repository of Traditional Ecological Knowledge” in the Journal of Ecological Anthropology, 2016.