This list was originally created thanks to a call to Twitter (RIP) to identify great resources for studying London landscape, architecture, and urbanism. Please let me know if you see anything significant that’s missing, and do let me know why it’s significant and what part of London it references. I have tried, wherever possible, not to link to IMDB, as it is owned by one of the billionaire mega-corporations that rule too much of our lives, but in some cases the only reference is there.

First off, I must make special mention of the BFI Britain on Film map. It’s a slightly clunky interface, but it allows a search of films set in Britain by location, and of course there are a vast number set in London: https://player.bfi.org.uk/britain-on-film/map#/54.69843416/-0.4924633970/6///. Also the website Reel Streets is a constantly growing resource which is searchable by region: https://www.reelstreets.com/

Films

15 Storeys High (BBC sitcom, 1998-2000) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/15_Storeys_High

All That Mighty Heart (R.K. Neilson-Baxter, 1962) ‘A British Transport Film’ A day in the life of London and the Home Counties in 1962, seen from the perspective of the use of London Transport facilities from buses and tubes to long distance coach routes. Accompanied by extracts from BBC radio. Watch it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kIgORp3Rvuc&ab_channel=JoanneHarris

An American Werewolf in London (John Landis, 1981) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0082010/ Locations lovingly detailed here: https://www.reelstreets.com/films/american-werewolf-in-london-an/ and hunted down like prey here: https://www.movielocationhunter.co.uk/show/movie/an-american-werewolf-in-london

The Angel Who Pawned Her Harp (Alan Bromly, 1954) Shot at the Angel in Islington and in Haringey. “An angel finds that she needs money to fulfill her mission on Earth. Her only solution to this problem is to pawn her harp.“–IMDB https://www.reelstreets.com/films/angel-who-pawned-her-harp-the/

The Arsenal Stadium Mystery (Thorold Dickinson, 1939) Filmed at Wembley. Just kidding. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/arsenal-stadium-mystery-the/

Attack the Block (Joe Cornish, 2011) Aliens invade the now-demolished Heygate Estate in Elephant and Castle. A “perfect allegory of estate-demolition and the stigmatization of black working class youths.” —Oli Mould: see his article here: https://filmopolis.co.uk/attack-the-block-review/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attack_the_Block

Babylon (Franco Rosso, 1982) The Black experience in the UK in the 80s, reggae, sound system culture, family drama, police brutality and much more. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/babylon/

The Bed Sitting Room (Richard Lester, 1969) Post-nuclear apocalyptic film. Features Aldwych Tube and a submerged St Paul’s Cathedral. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/bed-sitting-room-the/

Beautiful Thing (Hettie MacDonald ,1996) Gay coming of age story set in the Brutalist housing estate of Thamesmead. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beautiful_Thing_(film)

Bend it Like Beckham (Gurinder Chadha, 2002) Filmed in Hounslow, Hayes, and Southall. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bend_It_Like_Beckham

Les Bicyclettes de Belsize (Douglas Hickox, 1968) Shot in Hampstead. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/bicyclettes-de-belsize-les/

Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966) Filmed in several locations around London including Greenwich and Notting Hill. Opening scene is at The Economist Building in St. James. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/blow-up-2/

The Blue Lamp (Basil Dearden 1950) Fantastic views of Harrow Road and Warwick Avenue/ Maida Hill area. See the blog ‘The Blue Lamp Then and Now.’ https://www.reelstreets.com/films/blue-lamp-the/

Breaking and Entering (Anthony Minghella, 2006) Jude Law plays a landscape architect with an office in King’s Cross at the dawn of its gentrification. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breaking_and_Entering_(film)

Britain at Bay (Harry Watt, GPO Film Unit 1940) Big Ben pictured behind barbed wire. http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/1315472/index.html

Career Girls (Mike Leigh, 1997) In which a very 90s futures trader shows off his fancy Canary Wharf flat. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/career-girls/

Chameleon Soho (Paul Des Salles, 1979) This one’s hard for me to watch. So many great things that have been lost in just the last few years. The original Patisserie Valerie … sigh. View it for free here: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-chameleon-soho-1979-online

Children of Men (Alfonso Cuarón, 2006) Post-apocalyptic London in 2027 (we’re almost there) https://www.reelstreets.com/films/children-of-men/

The City (Ralph Elton, GPO Film Office1939) http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/999708/index.html

A City Crowned with Green (Reyner Banham, 1964) Watch it here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00sydsh/a-city-crowned-with-green

A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971) Scenes shot in Thamesmead. The ‘Ludovico Medical Facility’ is in fact the Brutalist lecture centre at Brunel University in Uxbridge by John Heywood/Sheppard Robson. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/clockwork-orange-a/

Cosh Boy (Lewis Gilbert, 1953) Scenes in Hammersmith and Battersea. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/cosh-boy-reboot/

Deep End (Jerzy Skolimowski, 1970) “15-year-old dropout Mike takes a job at Newford Baths, where inappropriate sexual behaviour abounds, and becomes obsessed with his coworker Susan.” https://www.reelstreets.com/films/deep-end/

Desmond’s (Channel 4 sitcom, 1989-1994) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desmond%27s

Doctor in the House (Ralph Thomas, 1954) Gower St, UCL Main Building and Quad (posing as ‘St Swithin’s Hospital’), and Cruciform building – also used in subsequent Doctor films https://www.reelstreets.com/films/doctor-in-the-house/

East Meets West (Herbert Mason, 1936) “The son of a wealthy and powerful sultan is carrying on an affair with the wife of an infamous criminal. The father determines to end the affair, erase the shame of his son and bring the criminal to justice.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Meets_West_(1936_film)

Expresso Bongo (Val Guest, 1959) – Mostly Soho, but also Pimlico and White City. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/expresso-bongo/

Fahrenheit 451 (François Truffaut, 1966) Lots of wonderful futuristic locations, but the Alton Estate in Roehampton is the star. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/fahrenheit-451/

Festival in London (Philip Leacock, 1951) Watch the film about the 1951 Festival in the National Archives collection here: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/films/1945to1951/filmpage_fil.htm

Free Cinema (BFI Box Set) http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/444789/index.html

Frenzy (Alfred Hitchcock, 1972) Misogynistic violence in pre-touristification Covent Garden. Fabulous shots along the Thames too. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/frenzy/

Gideon’s Way (TV Series, 1964-1966) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gideon%27s_Way

The Green Man (Robert Day and Basil Dearden, 1956) Shot largely in and around Holborn. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/green-man-the-2/

Harry Brown (Daniel Barber, 2009) Excessively violent revenge thriller set in the Heygate Estate at Elephant and Castle. Fulfills a checklist of Daily Mail stereotypes, cramming in stigmatisation and demonisation of social housing, the working class, and the young. It’s on this list because it’s useful to show how prejudice is mobilised against the urban fabric of working class neighbourhoods. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to learn this film was paid for in full by the real estate financiers who replaced the Heygate with ‘luxury’ flats. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Brown_(film)

Heart of the Angel (Mollie Dineen, 1989) – Documentary about Angel Tube station. Really good, acclaimed documentary and maker. Watch it here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0074tkn

Hidden City (Stephen Poliakoff, 1987) Wide variety of locations around London. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/hidden-city/

High Hopes (Mike Leigh, 1988). Filmed in King’s Cross and other locations. Lloyd’s Building in Leadenhall appears in a cameo. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/high-hopes/

High-Rise (Ben Wheatley, 2015). Ostensibly about London, but filmed in Belfast and Bangor. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-Rise_(film)

Hue and Cry (Charles Crichton, 1947) An Ealing comedy about children solving a heist, shot on location in a bombed out City/East End. Great, sweeping shots of the Docklands. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/hue-and-cry/

I Love This Dirty Town (Margaret Drabble, 1969) Watch it here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00rzvqv

It Always Rains on Sunday. I think this is in Camden.

It Always Rains on Sunday (Robert Hamer, 1947) Kentish Town and Whitechapel. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/it-always-rains-on-sunday/

Joanna (Michael Sarne, 1968) Multiple London locations including Paddington, Kensington Gore, and the South Bank. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/joanna/

Jubilee (Derek Jarman, 1978) Huge variety of London locations including Greenwich, Deptford, Kensington, and Bermondsey. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/jubilee/

A Kid for Two Farthings (Carol Reed, 1955) Many detailed scenes in Petticoat Lane. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/kid-for-two-farthings-a-2/

The Knack … and How to Get It (Richard Lester, 1965) Knightsbridge, Warwick Avenue, Campden Hill Water Works, Holland Park. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/knack-and-how-to-get-it-the/

Ladies Who Do (C.M. Pennington-Richards, 1963) Camberwell, Battersea, Kew, among others. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/ladies-who-do/

The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955) Alec Guinness and Peter Sellers in the classic Ealing Comedy set in King’s Cross. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/ladykillers-the/

Aerial view of King’s Cross from The Ladykillers

The Lavender Hill Mob (Charles Crichton, 1951) Lavender Hill plays itself in this classic heist movie; well, at least you think it would, but this is filmed in various locations including Gunnersbury Park and Notting Hill. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/lavender-hill-mob-the/

The Leather Boys (Sidney J. Furie, 1963) An early sympathetic portrayal of a gay character in British film. As it features motorcycling, there are many street locations across London from Kingston to Canning Town and some great shots of the venerable biker spot The Ace Café (still standing, but with altered signage). https://www.reelstreets.com/films/leather-boys-the/

The Lodger (Alfred Hitchcock, 1927) June Tripp and Ivor Novello in Alfred Hitchcock’s first suspense film, “a story of the the London fog”. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/lodger-the-1927/

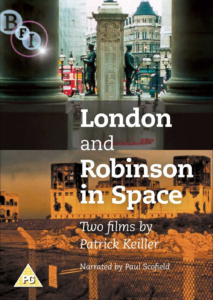

London, Robinson in Space, and Robinson in Ruins (Patrick Keiller 1994, 1997, and 2010). This trilogy comprises three of the finest films ever made about London. The first two are narrated by Paul Scofield and the third by Vanessa Redgrave. They express London through a landscape sensibility, unfolding meaning through relationships across vast time and space through Sebaldian methods that combine fact, fiction, and memoir. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_(1994_film)

London Can Take It (Harry Watt and Humphrey Jennings, GPO Film Unit, 1940) http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/443913/index.html

London Fields (Matthew Cullen, 2018) I have to admit that, from a cursory glance through the film stills on IMDB, this looks like a truly terrible film, but hey, it’s got a scene shot at the top of the Gherkin. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1273221/

London in the Raw (Arnold L. Miller and Norman Cohen, 1964) Exposé inspired by Mondo Cane. Followed by the sequel Primitive London (see below). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_in_the_Raw

The London Nobody Knows (Norman Cohen, 1969) An absolute classic, this, and an insightful document about London. With James Mason. Watch here: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x5h8w0m “A 45-minute trippy documentary of late 1960’s London and is a fascinating time capsule of the remnants of a bygone age before Londons’s extensive redevelopment in the late 1960’s.” https://www.reelstreets.com/films/london-nobody-knows-the/

London’s Green Heritage (Director unknown, 1948) A documentary about London’s parks. Watch it here: https://www.londonsscreenarchives.org.uk/title/1093/

London’s Green Heritage

London Symphony (Alex Barrett, 2017) A recent silent film in the ‘city symphony’ genre celebrating London. “A poetic journey through the life of a city”. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt6974916/

London: The Modern Babylon (Julien Temple, 2012) Archive footage and voiceovers construct this kaleidoscopic portrait of London. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1937419/

A London Trilogy ( Paul Kelly and Saint Etienne, 2013) Finisterre: A Film About London (2003) is probably the best of the three music-driven London films by the band Saint Etienne. It’s set in East London as is What Have You Done Today, Mervyn Day? (2005). This is Tomorrow (2007) features the renovations of the Festival Hall/Southbank Centre. They’re available in a box set as A London Trilogy: http://www.saintetienne.com/london-calling-a-london-trilogy/

The Long Arm (Charles Frend, 1956) West End, Chelsea, Great Queen Street, Hammersmith, and many other locations. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/long-arm-the-2/

The Long Good Friday (John Mackenzie, 1980) Rightfully celebrated gangster thriller set in London’s blasted docklands, starring Helen Mirren and Bob Hoskins. This is a must-see. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/long-good-friday-the/

Tower Bridge photo-bombs The Long Good Friday

Look Back in Anger (Tony Richardson, 1959) Atmospheric Holloway, Romford, Harlesden, Acton, and Dalston locations. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/look-back-in-anger/

The Magic Christian (Joseph McGrath, 1970) Chelsea, Fulham, and Putney. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/magic-christian-the/

A Man About the House (Leslie Arliss, 1947) St John’s Wood, Euston Road, Pompeii, and the Amalfi Coast (unfortunately the last two are not in London). https://www.reelstreets.com/films/man-about-the-house-a/

The Man Who Haunted Himself (Basil Dearden, 1970) City, South Bank, St James, Mayfair, Chiswick. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/man-who-haunted-himself-the/

Melody (Waris Hussein, 1971) Set in Lambeth. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/melody-aka-swalk/

Metro-land (Edward Mirzoeff, 1973) John Betjeman’s film poem and guide to the Metropolitan Line made for television. Watch it here: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x5i3sp7

Misfits (2009) Channel 4 drama set in Thamesmead. https://www.channel4.com/programmes/misfits

Momma Don’t Allow (Karel Reisz, 1956) This short film by the late great Karel Reisz is a perfect rendition of working-class youth having a night out in 1950’s London https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2b69e93c9d

Mona Lisa (Neil Jordan, 1986) Bob Hoskins may well be a synecdoche for London. This is another true great, that roves all over a luscious, grubby London with a coda in Brighton. Just check out all these glorious moments on Reelstreets: https://www.reelstreets.com/films/mona-lisa/

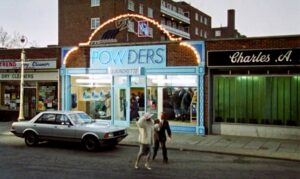

My Beautiful Laundrette (Stephen Frears, 1985) Punk meets Pakistani, queer love in a laundrette ensues. Totally wonderful. Particularly interesting in relation to Nine Elms development and what has been lost. There is an article by the BFI about the London locations of the film here: https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/my-beautiful-laundrette-locations https://www.reelstreets.com/films/my-beautiful-laundrette/

My Beautiful Laundrette, 11 Wilcox Road, Lambeth

Naked (Mike Leigh, 1993) Perhaps David Thewlis’s finest moment in film; he plays a repellent anti-hero. Shot in Dalston, Southwark, Soho, and Fitzrovia. Its most famous scene, an edgy encounter with a security guard, is shot in Ariel House (described as a “post-modernist gas chamber”) at 74a Charlotte Street, Fitzrovia. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0107653/

Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950) Shot in and around Leicester Square and Covent Garden, this film precedes Dassin’s heist film Rififi. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/night-and-the-city/

Nightbirds (Andy Milligan, 1970) Set in and around Spitalfields. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/nightbirds/

No Two the Same (1970) Ian Nairn’s Pimlico films on Churchill/Lillington Gardens; a moment perfectly caught. Watch for free here: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-ian-nairn-1970-online

Notting Hill (Roger Michell, 1999) Sentimental romcom set in West Ham. Just kidding. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/notting-hill/

The Old Kent Road (Van Dyke Brooke, 1912) Silent short film. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0222243/

The Old Kent Road (British Pathé, 1971) “Travelling shots from vehicle driving down Old Kent Road showing school, road systems, wasteland, shops, blocks of flats, pubs, bus stops and advertising hoardings. Various shots graffiti on front of shop reading “Millwall”. ” Watch it here: https://www.britishpathe.com/video/old-kent-road

The Old Kent Road (Ian Parkin, 2014) Documentary telling the story of one of London’s oldest roads. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4697238/

Oliver! (Carol Reed, 1968) All filmed in recreations of London on elaborate soundstages at Shepperton Studios, including a scene with a steam railway. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/oliver/

Omnibus: The River Bob Hoskins takes Barry Norman on a truly brilliant walk on the South Bank – the reality of redevelopment “makes the Long Good Friday look like a story out of Winnie the Pooh”. Watch it here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/hoskins-london/zmgmd6f

The Optimists of Nine Elms (Anthony Simmons, 1973) Battersea, Nine Elms, and Peter Sellers. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/optimists-of-nine-elms-the/

Ours to Keep (1985) Dan Cruickshank presents a BBC programme on the restoration of Georgian houses in Spitalfields. Watch it here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00t3f42/ours-to-keep-incomers

Paddington (Paul King, 2014) Views of various London sites: Paddington Station, obviously, and also the Natural History Museum. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1109624/

A Palace for Us (Tom Hunter, 2010) A short film about the lives of residents of Woodberry Down Estate in Hackney. Watch an excerpt here: https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/a-palace-for-us/ : http://www.tomhunter.org/a-palace-for-us/

Passport to Pimlico (Henry Cornelius, 1949) Pimlico becomes independent from the rest of Britain. Actually shot on a set built on a bomb site in Lambeth. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/passport-to-pimlico/

The Pedway: Elevating London (Chris Bevan Lee, 2013) Excellent short film about the elevated walkways still remaining in the City of London, originally planned to raise pedestrians up off the street. View it here: https://vimeo.com/80787092

Peeping Tom (Michael Powell, 1960) Much is filmed in and around Fitzrovia. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/peeping-tom/

Rathbone Place, Fitzrovia, as seen in Peeping Tom. The Newman Arms at the top of Newman Passage is visible to the centre left.

Perfect Friday (Peter Hall, 1970) Grovesnor Crescent, Hyde Park Corner. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/perfect-friday/

Performance (Donald Cammell & Nicolas Roeg, 1970) Various scenes all over London in this psychedelic classic. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/performance/

Permissive (Lindsay Shonteff, 1970) “Groupie girls who really want to make it big!” https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0066216/

Piccadilly (E.A. Dupont, 1929) Silent film starring Anna May Wong. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/piccadilly/

A Place to Go (Basil Dearden, 1963) Set in Bethnal Green. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/place-to-go-a/

The Ponds (Patrick McLennan & Samuel Smith, 2018) Documentary about the swimming ponds on Hampstead Heath. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7702314/

Pool of London (Basil Dearden, 1951) “A drama of the river underworld”. Wonderful locations shot in the City of London. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/pool-of-london-2/

Postcards from London (Steve McLean, 2018) Camp, colourful, queer sex work melodrama set in Soho. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postcards_from_London

Primitive London (Arnold Louis Miller, 1965) https://player.bfi.org.uk/rentals/film/watch-primitive-london-1965-online

The Proud City: A Plan for London (Ralph Keene, 1946) J.H. Forshaw and Patrick Abercrombie present the new (then) Plan for London. Available for free on the BFIPlayer here: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-proud-city-a-plan-for-london-1946-online

Patrick Abercrombie positively radiates midcentury male credibility.

Radio On (Christopher Petit, 1979) Atmospheric road movie with great shots of West London and a superb soundtrack (and a cameo appearance by a very young Sting). https://www.reelstreets.com/films/radio-on/

Robbery (Peter Yates, 1967) Railway heist movie about the Great Train Robbery. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/robbery/

Robinson in Ruins (Patrick Keiller, 2010) The third of the trilogy, and I think the best. Narrated by Vanessa Redgrave. See London https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1714893/

Robinson in Space (Patrick Keiller, 1997) see London. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120028/

Rocks (Sarah Gavron, 2019) Snapshot of east London life from a teenage girl’s perspective – collaboratively made. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rocks_(film)

Rude Boy (Jack Hazan & David Mingay, 1980) Film starring The Clash. Rated X presumably for a scene of simulated fellatio. Joe Strummer features prominently in a variety of London locations including Brixton and Covent Garden. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/rude-boy/

The Sandwich Man (Robert Hartford-Davis, 1966) Millwall, Somers Town, Lambeth, Billingsgate, London Wall, Tolworth, St Paul’s, and Holborn. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/sandwich-man-the/

Scandal (Michael Caton-Jones, 1989) South Bank and Bayswater. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/scandal/

The Scene from Melbury House (British Transport Films, 1973) Shot in fragments (with odds and ends of film stock) from the roof of Melbury House, just adjacent to Marylebone Station, this is a magical bird’s-eye and long-shot view of London. There is a description on the BFI website here and the film is available to view for free here: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-the-scene-from-melbury-house-1973-online

Battersea Power Station chuffing away beyond the clocktower of Marylebone Station in The Scene from Melbury House (1973).

Seance on a Wet Afternoon (Bryan Forbes, 1964) Filmed in Staines, Hythe End, and Wimbledon with notable scenes on the London Underground. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/seance-on-a-wet-afternoon/

Sebastian (David Greene, 1968) Cold war thriller with some great scenes on the walkways in the City of London. Film is very uneven but watchable. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/sebastian/

Seven Days to Noon (John Boulting and Roy Boulting, 1950) Central London. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/seven-days-to-noon/

Small Axe (Steve McQueen, 2020) A series of five utterly masterful short films set in London’s West Indian community. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Small_Axe_(anthology)

Shakespeare in Love (John Madden, 1998) Well, it wouldn’t be early Modern London without shots of the Globe Theatre, now would it? (Spoiler: not the original Globe) https://www.reelstreets.com/films/shakespeare-in-love-ready/

Sparrows Can’t Sing (Joan Littlewood, 1963) East End romp with Barbara Windsor. Shadwell, Woolwich, Stratford. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/sparrows-cant-sing-2/

The Street (Zed Nelson, 2019) Thoughtful portrait of working class life and encroaching gentrification on Hoxton Street. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Street_(2019_film)

Streetwise (Mark Phillips, 1996) Film about London cab drivers preparing for the comprehensive examination known as “The Knowledge”. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1306584/

Terry on the Fence (Frank Godwin, Children’s Film and Television Foundation, 1986) “A mixed-up, teenage runaway becomes involved with a tough teenage street gang and its lawless activities while trying to find a way to redeem himself.”–IMDB Set in London’s Docklands and much gentler than The Long Good Friday. Great aerial shots in the credits. Greenwich, Deptford, Poplar. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/terry-on-the-fence-childrens-film-foundation/

Thamesmead 1968 (Jack Saward-Greater London Council 1968) GLC film about the planning for the Thamesmead development. View for free here: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-thamesmead-1968-1968-online

That Kind of Girl (Gerry O’Hara, 1963) “Austrian au pair girl comes to London as the 60s are on the brink of swinging, dabbles in CND and receives a dose of VD.” — Reel Streets. Fitzrovia, Kensington, Chelsea. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/that-kind-of-girl/

To the World’s End: Scenes and Characters on a London Bus Route (BBC, 1985) This short film follows the route of the no. 31 bus from Camden Town to World’s End in Chelsea. View it here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0074ry7

Top People (ITV, 1960) Workers on London’s High Rises. https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2b79dd6806

Underground (Anthony Asquith, 1928) Chelsea, Bakerloo Line, Brompton Park Road https://www.reelstreets.com/films/underground/

Utopia London (Tom Cordell, 2010) Documentary about architects such as Kate Mackintosh who built some of London’s finest and most interesting social housing. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1757922/

We Are the Lambeth Boys (Karel Reisz 1959) Thoughtful and sympathetic portrayal of working class lives in Lambeth on the verge of the 1960s. View for free here: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-we-are-the-lambeth-boys-1959-online

We are the Lambeth Boys

The Winstanley Plays Itself (Aileen Reed) This wonderful short film from the Survey of London explores the 1960s Winstanley Estate in Battersea to great effect. View for free here: https://vimeo.com/102127150

Wonderland (Michael Winterbottom, 1999) Set in Soho, Vauxhall, Crystal Palace, Selhurst Park, and South Norwood. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/wonderland/

The Wrong Arm of the Law (Cliff Owen, 1963) Soho, Mayfair, Buckinghamshire. https://www.reelstreets.com/films/wrong-arm-of-the-law-the/

Young Soul Rebels (Isaac Julien,1991) Superbly stylish Black and queer (and quintessentially London) story. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Young_Soul_Rebels

Films for teaching architecture and planning: there’s a really great crowd-sourced and annotated list here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/19Sgcor0JF8rBBdrkDxsQAjlWWWzbRaIQRU1i2XluGEA/edit

And here’s a very thoughtful list by Jill Stewart of documentary films about housing, many of which feature London: https://www.jillstewarthousing.co.uk/learning-from-documentary-films/

Note: I’ve now removed the book and map lists to keep this section focused on film. I’ll get those posted up again under a different heading soon.

Thanks to:

@anonomia, @BardenGridge, @bonapart100, @clashy_girl, @DaubeneyT, @DawsonsHeights, @DollyG66, @EastLondonGroup, @ed25terror, @HistoryTown, @infrahumano, @KinondoniDSM,@linea_at_ftc, @Lucotter1, @Megthelibraria1, @planning4pubs, @psychojography, @stef18881, @terry61021, @tomdanewag, @TomPoyn, @un_Arch, @urbanpastoral, @WestminP, A2 Architects, Pam E. Alexander, Peter Barber, Myles Bartoli, Hannes Baumann, Duncan Bell, Alan Benzie, Matthew Berry, Danny Birchall, Gerald Blessington, Adam Borch, Iain Borden, Steve Bowbrick, Nick Bowes, Kathleen Brentford, Aidan Budd, Lucy Bullivant, Craig Burston, Eric Dolph, Richard Brown, Rob Cave, Aditya Chakrabortty, Tom Chivers, Shane Clarke, Robert Clayton, Steve Cole, CPRE London, Alan Crawford, Gillian Darley, Andrew Demetrius, Demolition Watch London, Directions Bas, Paul Dobraszczyk, Philip Downer, Michael Edwards, Fiona Fieber, Jason Finch, Suzy Fisher, Jonathan Ford, Justin Fowler, Samantha M Fox, Adam Nathaniel Furman, Leonid Furr, Rachel Genn, Alice Grahame, John Grindrod, Felicity Hall, Lucy Hall, Dan Hancox, Ewan Hannah, Danielle Hewitt, Frederick Guy Holmes, Garry Hunter, Colin Hynson, Jake Ireland, Catrin James, Bryony Jameson, Will Jennings, Oskar Johanson, Lyndon Jones, Just Space, Tom Keene, Richard Knight, Bec Lambert, David Landau, Paul Lincoln, Andrew Lockett, Freddie Lombard, Carya Maharja, Thomas and Ingrid Marlow, Alison Martin, Matty Massi, Christopher McAteer, Ross McKinley, Darran McLaughlin, The Modernist Magazine, George Morgan, Janice Morphet, Max Morwell, Tim Morton, Oli Mould, Andrew John Nelmes, Nita Newman, Miranda Nieboer, Nilesh Patel, Jane Petrie, Christopher Pfiffner, Praxis Architecture, Emma Quinn, Katherine Ramsey, Omer Raz, Nicola Read, Tadeáš Ríha, Ben Rimmer, Sam Roberts (Ghost Signs), Suzy Robinson, Bryony Rudkin, Sibyl Ruth, Robert Sakula, David Samson, Jon Savage, Fred Scharmen, C.J. Schüler, Catherine Slessor, Bob L. Smith, Jonny Smith, Steve Smith, Jill Stewart, Matthew Sweet, Mark Tewdwr-Jones, Phil Tinline, Matthew Turner, Kieron Tyler, Steve Walker, Paul Watt, S.W. Whiteley, Owain D.H. Williams, Stacey N. Wing, Alan Wylie, Gail Wylie, Andy Yan, Alison Young