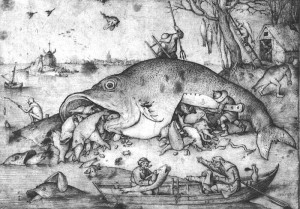

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s ‘Big Fish Eat Little Fish’. In an increasingly predatory political world, we need professions more than ever.

“A Word …” is my quarterly column for Landscape: The Journal of the Landscape Institute. Here in the Spring 2016 issue I address the importance of professions and institutions.

In the middle of the 17th century, at the dawn of modernity, the philosopher Thomas Hobbes, in his Leviathan, described human relations as bellum omnium contra omnes – a war of all against all – an idea which subsequently came to underpin dog-eat-dog conceptions of social Darwinism, and which characterises the mindset that made possible the transatlantic slave trade and the enclosures and clearances in early capitalism. Contrasted to this are the premodern commons, those shared lands and practices that were the basis for communal well-being and wealth, unus pro omnibus, omnes pro uno – all for one and one for all. The dog-eating dogs continue to consume each other and to enclose the commons globally, and the ideology that allows it still echoes Hobbes. It is known as competitive individualism and it is the foundation for neoliberalism, the ideology under which we have seen governments everywhere become more authoritarian and market-driven.

It is commonly assumed that the commons are historic conditions, but people still work together everywhere for mutual advantage, and we might even regard professions as types of commons. What does a profession do and how does it function? It consists of a variety of interlinked supports and guarantees: it ensures trust both internally and externally by providing the certification of the group and adherence to a robust code of ethics; it provides support for students and young professionals through education, training, and/or apprenticeships; it provides promotion, advocacy, and communications; it lobbies in government; it provides statutory protection for the work of its professionals. Last but not least, it provides for togetherness and sharing of ideas, friendship, and the common good. Professions thus have great importance both for their members and as models of what society can and should be.

Professions and institutions of all sorts are now increasingly under threat from competitive individualism, however. The relentless intensity of our working lives makes it ever more difficult for us to make time for togetherness and sharing. Downward pressure on professional wages in many sectors makes long periods of time and quantities of money spent on education and qualification seem wasteful instead of the vital structure of our mutual guarantee. Finally, and probably not only, our perception of society as composed of disconnected individuals means that we are putting greater trust in crowd-sourced certification (Trip Advisor springs to mind, with its five-star ratings for popular but unexciting restaurants) rather than expert or institutional judgment.

Competitive individualism complicates professions even further. We tend to see achievements as the work of disconnected and miraculously inspired individuals – this is evident in the trend toward starchitecture – rather than as the work of professions and the sharing and supporting networks engendered by them, from education to practice. We have come to see value as being created by the lone genius rather than by a great collective work over many years.

It may be that the multiple threats which professions face, as they are presently constituted, and in a winner-takes-all world, will be enough to overwhelm them completely. Or they may change and adapt to new forms that we cannot yet predict. Or finally we may decide that we need to make a case for the continued survival of professions and stand stalwart together in defence of the idea of mutual aid. As for me, I know I’m one for all.