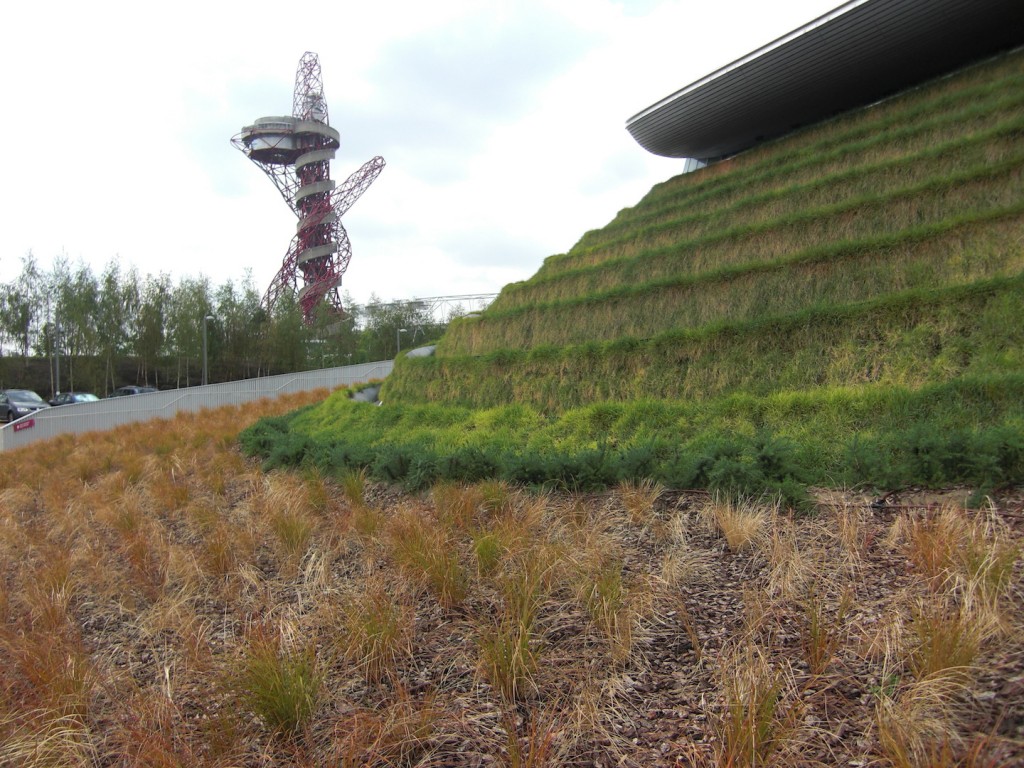

“… that awful loopy red thing” – The Orbit – at the site of the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic games in London’s Stratford.

“A Word …” is my quarterly column for Landscape: The Journal of the Landscape Institute. Here in the Autumn 2014 issue I demolish a couple of Norman Foster buildings and “…that awful loopy red thing”.

Our cities are places defined by what the architectural historian Spiro Kostof called ‘a certain energised crowding’. This is an understated way of describing the intoxicating density and intensity of action, interaction, and spectacle that defines the urban experience. The fine-grained texture of our cities, though, is not one of continuous hyper-stimulation. Even in the wealthiest and most congested city centres, where the greatest number of buildings and other elements of urban topography vie for attention, there are still calm and dignified stretches of unified cityscape.

The same concentration of totemic features that many cities display is evident in the design of theme parks, which are typically a dizzying mishmash of emblematic structures, logos, and loaded imagery. The back of one attraction is the front of another, and no matter which way one turns there is a landmark loaded with signification. This way Paris, that way Venice, over here Tomorrowland, and here dinosaurs grazing in primordial swamps. Both cities and theme parks overload the senses, resulting in an intoxication that can be euphoric or disorientating or both. Each requires an eventual escape. With a theme park this is a simple matter of finding the exit, but with a city those mechanisms for release must be found within. The city as a whole cannot be constantly and everywhere in a state

of climax.

Landscape architects, within planning processes in urban design, need to be constantly vigilant to carefully moderate the urges of both clients and of building architects to make every edifice a monument or a logo. Even the most celebrated architects are guilty of designing objects displayed on plinths that are utterly acontextual. When a number of such buildings are crammed together, as they are in such orgies of bling as Dubai, the overall effect is camp writ large – as though every street corner were one of Liberace’s extravagantly jewelled knuckles.

A good landmark, whether a building, a sculpture, or a feature within a park, should be of its place and for its place, or perhaps in radical contrast to its place; but overall the effect should be to punctuate and to anchor. In striving for logo buildings many architects have gone too far and plugged up a landscape with buildings like bungs. Foster’s London City Hall and his Sage in Gateshead are both rounded in plan and section and both are designed as though on plinths. Neither building will allow for the city to flex and change around it. Neither, I would imagine, will still be standing in twenty years’ time. Neither is as much a landmark, a marker of place, as it is a monument to itself. Rather than the grain of sand that forms a pearl, each is an irritating foreign body that will eventually be rejected.

Note how I’ve mixed my metaphors? I have bungs and corks, sand and pearls, orgies and jewels and knuckles. I’ve spangled this column with the same sort of overwrought conceptualism that is so problematic in our cities. There are places, though, where this approach can actually work. This is in a park where many conceptual structures can be a collection of follies. London’s Olympic Park is a good example, where a stadium, a ‘wave’, a ‘Pringle’ and that awful loopy red thing all conspire to provide an exquisite balance between theme park and peaceful haven, reinventing the grand tradition of Stowe, Stourhead, Castle Howard, and Kew. Kew has only preserved a fraction of the number of follies it had when it was built (there were once fully twenty classical temples), so there is comfort that Stratford’s ensemble will still have integrity when the Orbit is demolished.