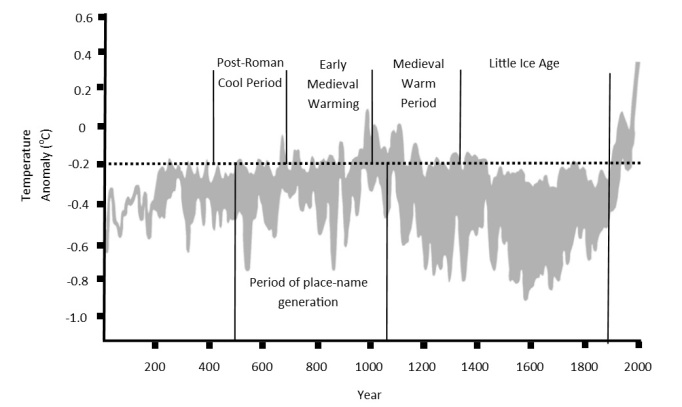

This article first appeared in the January 2017 issue of Landscape Architecture Magazine

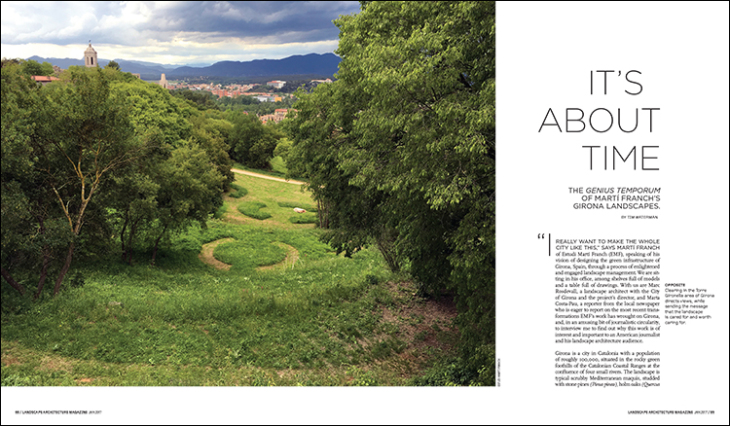

“I really want to make the whole city like this,” says Martí Franch of Estudi Martí Franch (EMF), speaking of his vision of designing the green infrastructure of Girona, Spain, through a process of enlightened and engaged landscape management. We are sitting in his office, among shelves full of models and a table full of drawings. With us are Marc Rosdevall, a landscape architect with the City of Girona and the project’s director, and Marta Costa-Pau, a reporter from the local newspaper who is eager to report on the most recent transformations EMF’s work has wrought on Girona, and, in an amusing bit of journalistic circularity, to interview me to find out why this work is of interest and important to an American journalist and his landscape architecture audience.

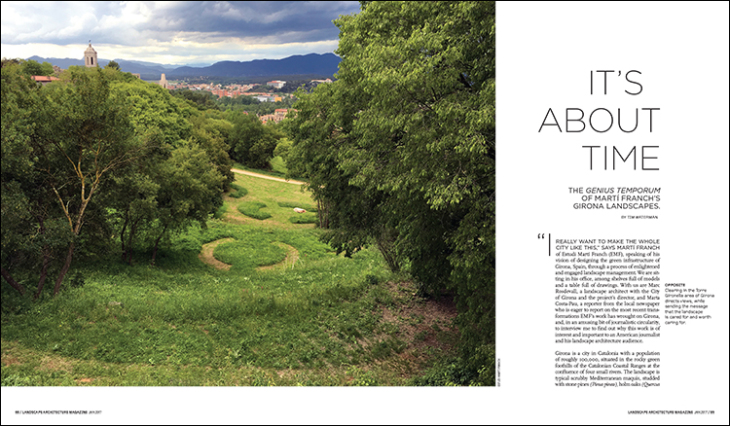

Girona is a city in Catalonia with a population of roughly 100,000, situated in the rocky green foothills of the Catalonian Coastal Ranges at the confluence of four small rivers. The landscape is typical scrubby Mediterranean maquis, studded with stone pines (Pinus pinea), holm oaks (Quercus ilex), and the inevitable and omnipresent formal Italian cypresses (Cupressus sempervirens), which have an air of nervous, attendant stiffness in the loosely informal Catalonian landscape, like butlers at a barn dance. When I visit in late spring, there is a festival of flowers in the central city called the Temps de Flors. It’s a mix of floral installations that range from the highly professional and artistic to the desperately tacky. However, in the spirit of spring, with the soft air at skin temperature, the rivers full of water, and the maquis replete with shades of fresh and fleshy greens on the hills above the honey-colored stone of the old town, the exuberant bad taste is forgivable and welcome, even charming.

The Can Colomer meadow during its periodic mowing and maintenance. Image courtesy of Estudi Marti Franch.

The town’s generous web of green spaces reflects its topography, with concentrations of agricultural terraces on the hillsides, and the valleys between full of lush and wild plants all pushing into the densely built fabric of the town. It gently pushes back, curving into the green. All this gentle beauty belies a much less idyllic history of the landscape’s continual mistreatment. Girona’s citizenry has not recently had a virtuous relationship with the land: “The forest is for violation and for dropping fridges,” says Franch, referring to the long-standing problem of the regular dumping of building and household waste and appliances willy-nilly on the city’s fringe. His goal is to reveal the beauty of the whole of Girona’s landscape, opening up strategic views, providing access to the rivers, installing pathways and resting places, and, in doing so, encouraging the populace to value its surroundings more and creating a new relationship between the city and its surroundings. Even in the early stages of his project, he notes, there has been a visible reduction in the amount of dumping.

Beginning in September 2014, Franch embedded himself in processes of management across Girona, working closely with the city’s landscape maintenance teams, known locally as “brigades,” in particular with Jordi Batallé, the charismatic and energetic lead (comisari) of the brigades. Rosdevall describes the early stages, in which his superiors decided they would humor Franch in what they assumed was a quixotic journey. “My boss didn’t expect much from Martí. ‘Leave him alone and don’t spend any money,’ he said.” Franch, inspired by the approaches exemplified by the work of Gilles Clément in France, wanted to generate design from a direct engagement with site. He doesn’t see himself as a lone practitioner or a “master”; rather, he works in an informed conversation with the ecology of his practice, the ecology of the site, and the ecology of ideas in the world of landscape architecture.

Clément, when describing his approach in his 2015 book, The Planetary Garden and Other Writings, could be speaking for Franch, too: “For a long time I gardened without clarifying my ideas. Nevertheless, there were plenty of standpoints: to conserve the diversity already present, to increase it, to utilize the energy inherent in the species, not to use opposing energies unnecessarily, and to end up with a pledge that I repeat as often as necessary: to do as much as possible with, and as little as possible against.”

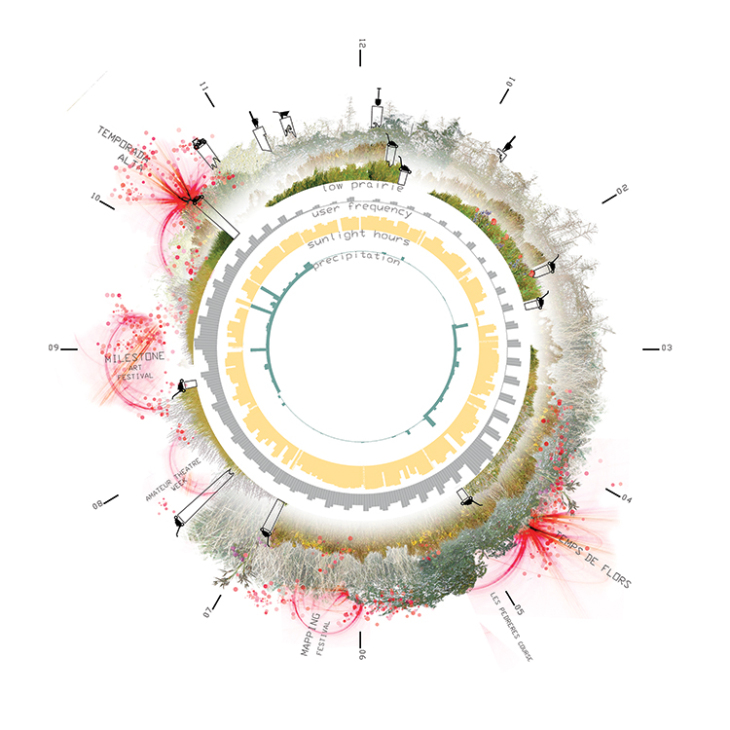

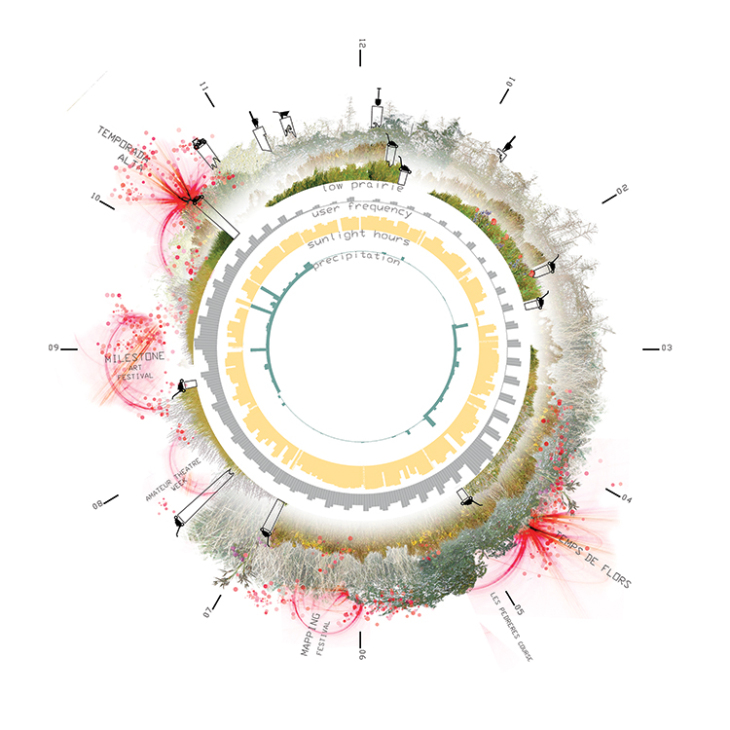

An annual diagram of maintenance including mowing and planting, growth of vegetation, sunlight hours, and other variables. Festivals, when maintenance brigades are busy, are shown as red sunspots. Image courtesy of Estudi Marti Franch.

Franch’s work in Girona is healing, connective, and narrative. The project can only loosely be called a master plan. What he has created is a series of walking loops, itineraries that knit Girona’s neighborhoods together, but these come together on the ground more than in the plan. “The final drawing is almost the as-built,” Franch says. The work begins on site, to understand the topography, hydrography, and viewsheds. With the maintenance brigades, he begins an active process of clearing, mowing, pruning, and cleaning. “The main thing we do is subtraction,” he says. Bearing in mind a framework of green infrastructure coaxed into presence by following the existing topography and river corridors, sites are cleared, trees are limbed up, and connections are made apparent. Only then, for the future management practice, is the work transferred to plan and section. In essence what is created is an action plan, not a master plan.

View from a terrace on the Torre Gironella itinerary. In the foreground is the barrel arch of the water mine roof. Image courtesy of Estudi Marti Franch.

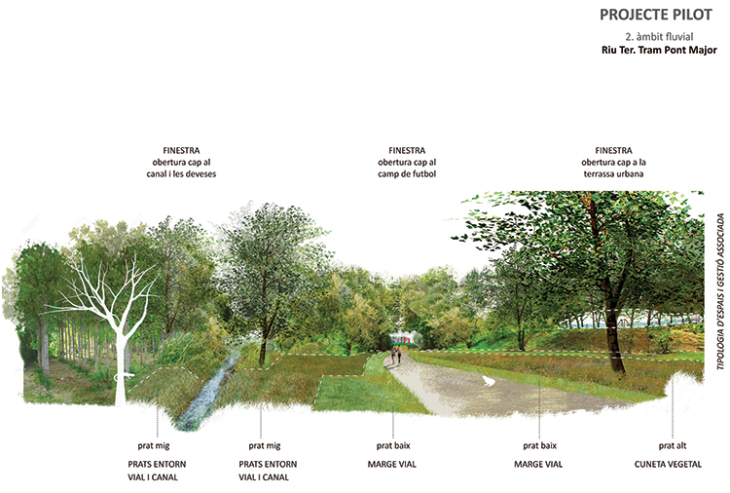

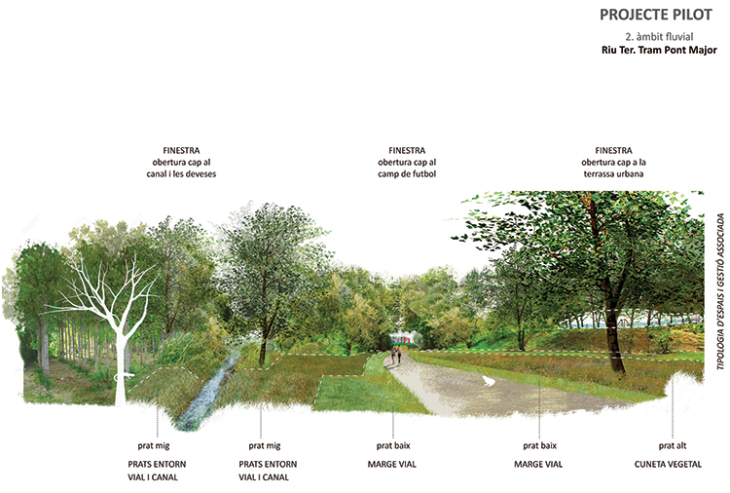

A striking example of the approach is the “shore edge” project, on the bank of the River Ter opposite the historic center of Girona. The district has had shady associations, appropriate to its formerly overgrown character, but it is now part of a legible riverside itinerary. Limbing up and clearing trees and shrubbery pulls the eye and the walker along the path with cool and luscious glimpses of the burbling river glinting in the sunlight. Where the path once followed a ruler-straight maintenance road, glaringly paved in white gravel, there is now a parallel route that brings people into the space of the river. It is palpably cooler, shaded. The river becomes audible, a balm to the senses.

This path leads to a newly created beach. Since the river was dammed, the natural scouring action of the river ceased to expose it, but through a process of clearing and rototilling, a gentle forest beach, softly shaded, allows ample room for play and relaxation. For the festival of flowers, the Temps de Flors, a lifeguard’s chair has been installed, a gleeful marker of the new mood introduced here, and a sprinkling of beach chairs adds color and life. Many are occupied, even on our weekday visit. They’re examples of what Franch calls “confetti,” small, irregular site interventions that give visitors occasional reminders of the fact of design. These can be sculptures, furniture, stumps left for climbing, almost anything. Visitors themselves become confetti in this setting. We approach a man in a motorized wheelchair, which has negotiated the sand successfully. He greets us with pleasure, and speaks of his pride in how the space has been transformed and how his daily excursions here have been improved. Equally important is his influence on the site, in which his regular presence serves as a daily marker of safety and comfort for others.

Girona green infrastructure and walking itineraries.

As we leave the shore edge, we pass a nightclub (“Pandora”) advertising exotic dancers, indicative of the uses to which this neighborhood had previously lent itself. The nightclub had opposed the improvements to the site, which included some loss of unsightly parking spaces along the river, but this year for the first time it’s decked its balcony with flowers for the festival.

Franch’s understated approach is not geared toward big wins—spending concentrated on visible central sites with sculptural and photogenic results, which are so often what politicians prefer to support, but it has captured the imagination of the area’s politicians. We have lunch with Narcís Sastre, the Girona city councilman responsible for landscape and urban habitat, on the terrace at the El Cul del Mon restaurant just outside town, and he tells us his reaction to Franch’s quiet, covert work. “When I first saw the meadows, I wondered what was happening. Once I knew, I wanted to spread it around the city.” Since then, the city’s mayor, Marta Madrenas i Mir, has also become a supporter. The “big win” with Franch’s designs is across the whole city and on every constituent’s doorstep, or at least it will be once all the looping landscape itineraries are created. What politician could resist such immediate, inexpensive, and widespread impact? When I talk about how many small projects can add up to big things, Franch grins and corrects me: “This is not a series of small projects. It is the biggest project in Girona ever.”

Martí Franch in the EMF office, Girona. Photo by Tim Waterman.

After lunch we climb from the valley to a hilltop overlooking Girona to see further interventions of this biggest project ever. Past a well-established and comfortably eclectic former favela, we come to signage indicating we are at the head of a “water mine.” Franch has created an itinerary that includes its edge. The water mine is a curiosity—it is a horizontal well that follows the contour of an agricultural terrace. Along our route, the edge of the terrace is marked by the barrel-arched roof of the tunnel, punctuated with chimneys which I speculate may work in the manner of a qanat, using air pressure to push water along to augment the sluggish movement caused by the infinitesimally slight gradient.

Postcard-worthy views open to the city and cathedral below as we move from an olive orchard abutting the water mine up to higher terraces. A steely blue-black thunderhead has filled the sky on the other side of the valley below, so we enjoy the view for only a moment, and hurry back through a tunnel of holm oaks formed by yet more judicious pruning. Thunder and lightning and the crepuscular light of the tunnel draw attention to how the nature of the itinerary is shaped not merely by place, space, and movement, but also by shifts of time and weather that animate the space. Fat, cold raindrops begin to slap down on us.

The drawings for the shore edge project serve first as plans for action and maintenance, and then only later add up to a master plan. Image courtesy of Estudi Marti Franch.

Franch’s management-based, hands-on methods have led him to try to find a new term analogous to genius loci that speaks of a deep understanding of diurnal and nocturnal cycles, weather, the seasons, and cycles of work and play framed by such markers as harvests and festivals. He suggests genius tempi, and I venture that zeitgeist fulfills at least part of that sense. We both like that each term contains time, presence of mind, spirits, and ghosts in their etymological derivations. Later, to find the right term, I ask the help of a friend, C. A. E. Luschnig, a classicist and etymologist. “Well,” she tells me, “tempi is not correct. The genitive of tempus is temporis, tempus being a neuter noun of the third declension. Maybe temporum (the genitive plural) would work better. Tempus has a full range of meanings including season, lifetime, the times.” This seems to crack the problem and to improve on it beyond our expectations—the term we were looking for was “the genius of time,” but conceiving of time as plural and nested is even better. Thus to add to genius loci, we now have genius temporum, the genius of times.

There is genius, too, in Franch’s propensity for action first and reflection alongside and after. He knows action is necessary, and his project is to learn by doing. There is no possibility of “analysis paralysis” because analysis, evaluation, design, and action are all part of the same impetus and bound up in the same nexus of energy. There is generative genius (or perhaps what Brian Eno calls “scenius”) in the collaboration, in the fact that the project’s ownership, design, and management are distributed and shared. The collaboration and co-creation mean that the design is not a totalizing one, but that it is a set of ways of acting and shaping in accord with changing uses and ecologies over time, perhaps beyond the lifetimes of all concerned. There is genius, finally, in the project’s tacit insistence that we must rethink the timescales, budgets, and commissioning of projects to embrace much more embedded and long-term practices of landscape management and design. Beyond the “big win” there is something at once softer and sweeter and more rich and grand that can develop in the sets of relationships through which we build great cities. In Girona, the genius of the place and of times—genius loci and genius temporum—are conspiring to create the city as a work of landscape art for the ages.