This is published in the new journal Testing-Ground, by the Advanced Landscape and Urbanism research group in the Department of Architecture and Landscape at the University of Greenwich, London.

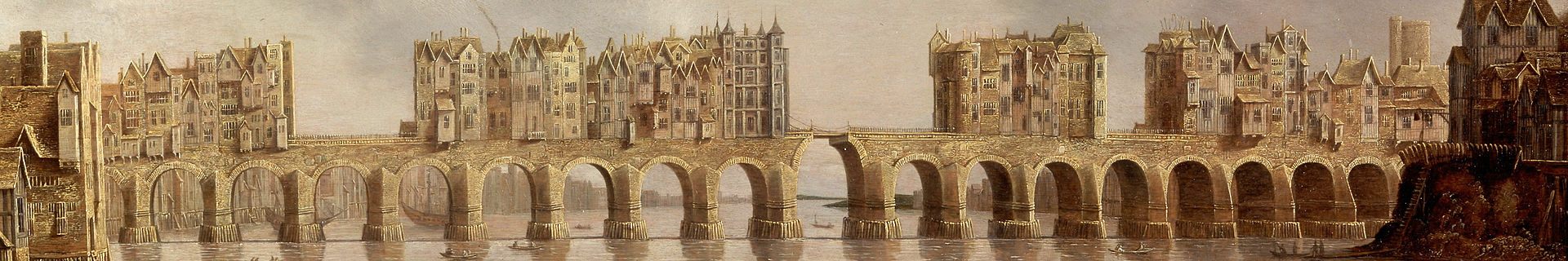

Detail of Old London Bridge on 1632 oil painting “View of London Bridge” by Claude de Jongh. Image from Wikimedia

Nearly sixty years ago, J.B. Jackson wrote one of the most insightful essays about landscape ever written, “The Stranger’s Path”. Jackson’s warm, gentle, and wise voice and keen observation have been constants in my career as a landscape architect and writer, and I offer the following piece as a kind of fugue, a flowing together of Jackson’s voice into mine, in the way that so many stories flow together in the city along the Stranger’s Path. Our dearest hopes for the future will always evolve from the places and the voices of our past. The city is a cosmopolitan story we write together, and so many of us have come there to write it as strangers.

Spokane, Washington, 1986

In what was, I think, the spring of 1986, my good friend Lisa and I ran away from the small town of Moscow, Idaho where we lived and went to high school together, and spent the day in Spokane, Washington. Spokane in the 1980s was a city only in shape, hollowed out by suburban expansion as well as an economy depressed over most of the twentieth century, though it had briefly stuttered into faltering recovery in the late 60s and 70s. For youngsters like us, with sarcastic anti-establishment attitudes, vertical hair-sprayed hair, and cassettes of obscure German industrial music in our Walkmans it was precisely Spokane’s grittiness that gave us both something to sneer at and to revel in. In Moscow, my friends and I would spend hours mooching around by the railway tracks, and exploring abandoned grain elevators and empty farmhouses, participating in the birth of an aesthetic based in the blasted remnants of rust-belt style decline and the demise of the small farm and farmer’s cooperative.

In Spokane these same forces were writ slightly larger, and the modern and postmodern buildings and landscapes produced in its short recovery were also empty and decaying. Spokane possesses one of the most extensive ‘skywalk’ systems in the USA, built around the time it hosted the environmentally-themed World Expo of 1974. Presumably grown from the Corbusian ideal of the ‘death of the street’, but also in defence against the area’s frigid winters, this shopping-mall-in-the-sky had first killed the streets below, then slowly killed itself. Lisa and I wandered its empty corridors eating chocolate-covered espresso beans and contemplating a seemingly post-apocalyptic cityscape from which all the citizens had simply disappeared.

A few streets away, at the Greyhound bus station, which was full, not of travellers, but of people trapped by permanent transience and precarity, and the smell of urine and fear, we wondered together whether bus stations, once planted, would spread their black tendrils of decay into the neighbouring soil; bad seeds that would ensure a continuously poisonous urban harvest for an area. Lisa and I sat on the pavement and sang a comic jingle together from the Sex Pistols movie Sid and Nancy, “I want a job, I want a job / I want a good job, I want a job / one that satisfies / my artistic needs.” We laughed together at the irony of the postmodern condition, savvy, world-weary punks.

“We are welcomed to the city by a smiling landscape of parking lots, warehouses, pot-holed and weed-grown streets, where isolated filling stations and quick-lunch counters are scattered among cinders like survivals of a bombing raid.”

No matter how blasé we pretended to each other to be, though, this was one of our first, rare moments of escape from home without our families. Rather than being swept solicitously past the iniquitous and ubiquitous head shops and adult book stores of the Stranger’s Path, we were now free to stand and stare at them, even enter them. Though we pretended we’d seen it all, we hadn’t really seen anything yet, certainly not in Moscow, Idaho. We were both making a time-honoured exchange with the city of Spokane; its secrets and lures for our inquisitiveness and invention. But poor Spokane—where Jackson’s ideal Stranger’s Path would lead us from potholes to a clean, bright city centre, Spokane’s Path at the time only led to a gaping absence where that centre should have been.

“[I]s it not one of the chief functions of the city to exchange as well as to receive? … These characteristics are worth bearing in mind, for they make the Path in the average small city what it now is: loud, tawdry, down-at-the-heel, full of dives and small catchpenny businesses, and (in the eyes of the uptown residential white-collar element) more than a little shady and dangerous.”

London, England, 2015

It’s Saturday the 14th of November 2015, and there is a steady rain. I’m starting a short walk from the base of Christopher Wren’s monument to the great fire of London, just at the intersection of London’s two most venerable Stranger’s Paths: London Bridge, for 700 years the only dry crossing of this reach of the Thames, and, of course, the River Thames itself. London has many Stranger’s Paths, which now include some routes oddly distended by public transport. Heathrow Airport, for example, sits amidst a vast terrain of potholes and parking, but travellers smear quickly across the suburbs via the Piccadilly Line or the Heathrow Express to eventually rejoin the Stranger’s Path in Earl’s Court or Paddington, each place raffish and lightly sleazy. The Borough High Street and London Bridge are still part of continuous Stranger’s Paths that, from Borough, fan out into Kent, Surrey, and East and West Sussex. I’m walking the stranger’s path out of the city, because now I’m a long time resident here, a Londoner as much as any other, it doesn’t make sense to me to walk the Stranger’s Path from the view of one entering. I will walk from the civic centre, that which absorbs, towards the periphery and beyond, from which the Path flows.

“The simile was further that of a stream which empties into no basin or lake, merely evaporating into the city or perhaps rising to the surface once more outside of town along some highway strip; and it is this lack of a final, well-defined objective that prevents the Path from serving an even more important role in the community and that tends to make it a poor-man’s district.”

Vistas in the City of London, with its tangled, medieval streets, are tightly enclosed. As one approaches London Bridge from the City of London along King William Street, the view expands dramatically. It is possible, here, to quickly comprehend the topography; the high north bank and the once-marshy south bank. The surface of London Bridge, a very clean plane, emphasises the horizontal and draws the eye out over the river. The water is shining as the sun breaks through the day’s dark, moist clouds. To the east, the Tower of London with flags waving. When London Bridge was crowned with its twin walls of houses, shops, and chapels this experience would have been very different. Before 1760-61, when the bridge was cleared of these habitable encrustations, and at the height of British naval power and transatlantic shipping, it must have been possible to catch glimpses from the crowded bridge, between the buildings, out to countless masts and ship’s decks forming an unbroken but uneven ground where now there is open water. Out the gate to the south, one would have passed under the cautionary severed heads of the executed, held aloft on pikes, signifying, perhaps, that the rule of order was rather weaker outside the gate than it was inside. Outside we would find the petty criminals, hucksters and whores, bishop-pimps, betting, drinking, and theatrical acts of all scales. On the south bank I reach the Borough High Street, its narrow footpaths jostling with people and its streets full of cars splashing through puddles gurgling up onto the curbs.

“The sidewalks are lined with small shops, bars, stalls, dance halls, movies, booths lighted by acetylene lamps; and everywhere are strange faces, strange costumes, strange and delightful impressions. To walk up such a street into the quieter, more formal part of town is to be part of a procession, part of a ceaseless ceremony of being initiated into the city and of rededicating the city itself.”

The Borough High Street and the myriad alleyways feeding into it are a writing and rewriting of the dialogue between congestion and commerce. A succession of narrow courts and alleys open up with only a building’s width between them. On a map, they appear like the teeth of combs, and they echo the parallel streets that once thronged perpendicular to the Thames, pulsing with a constant flow of people and goods from across the heaving seas. This whole place Jackson might have described as ‘honky-tonk’, and despite recent attempts to Manhattanise the area, I have hopes that it will retain its rough-and-tumble demeanour. The incredibly fine urban grain here reminds us that not only would these streets have been congested, but so would the commerce itself, with many businesses not wider than a person’s girth—and the prostitutes, of course, themselves commodities—‘commodity’ even being a name for their most private parts. The prostitute’s business fits precisely the space of her body. The carts drawing goods into the city to discharge in its markets would have been constantly clutched at and called to from these many stalls, perhaps most when the carts were returning empty and the purses were full; bellies filling, balls emptying; the city’s carnal and pecuniary tides are one.

The George, down one of these narrow side streets, is a rare survivor from the seventeenth century, and its history is longer—its original building was burnt. It is a galleried coaching inn, decked with balustrades on all levels from which to watch the comings and goings of horses and carriages below. Its interior is as intricately wrought as the streets outside. There are grand rooms and snug corners and stairways that allow glimpses of action above and below and which carry snatches of laughter from floor to floor. It’s full, loud, and friendly today with big groups crowding around tables filled with food and ale. It’s a dry spot to wet the innards, and my glass of Southwark Porter goes down a treat as I write, perched on the edge of a high bench with my notebook on a sticky table. The men next to me are talking about women, then about smoked meats.

“For my part, I cannot conceive of any large community surviving without this ceaseless influx of new wants, new ideas, new manners, new strength, and so I cannot conceive of a city without some section corresponding to the Path.”

When I leave The George, the beer has gone cold in my belly and rainy day melancholy has begun to take hold of me. Just to the south a hoarding has gone up around a large building site. Signs show images of the excavations that preceded the construction; foundations and walls closely stacked parallel and perpendicular layer after layer, generation after generation. Somewhere they begin in the silty ooze this part of the city is mired in. They are a reminder that the trajectories we inscribe have been written over centuries. As a species we don’t simply leave trails on the surface, but also below and above. When I look through the windows cut in the hoarding, I see all that is now gone, and sheet pilings line the edge of a vast, clean pit with freshly poured concrete curing at its bottom.

At last I arrive at the Marshalsea Prison wall, a place I have brought numerous visitors and guests because it is a place where you can feel the full weight of London’s terrible past. This blackened and dreadful high wall, studded with occasional spikes and rings, was the outer wall of the prison in which Charles Dickens’ father was incarcerated, amongst many others of London’s wretched. A site redolent of woe. Today, as the rain falls, I arrive to find the wall ‘restored’ and almost completely rebuilt, still solid and massive, but clean and crisp and regular. I knew I would find it this way, as I had caught a glimpse of this atrocity of cleansing while it was underway, again behind hoardings, but I’m still unprepared for the magnitude of the loss now that the hoardings have been removed. All its presence, its meaning, has been washed away, scrubbed away, normalised. That cruel history that called out to every visitor, “Never again!” has been whitewashed. What once was chillingly, silently eloquent is now merely mute. I stand in front of the wall and I can’t stop the tears welling up in my eyes.

Afterwards I wander aimlessly through the Borough Market, pushing through the crowds, and then cross the river at the Southwark Bridge, where the tide is high and the river is brimming with water that looks like cold, milky tea. Behind a glass curtain wall in a new restaurant in a new building near St Paul’s, a woman with shining hair and perfect teeth is laughing in a way that shows practiced charm, but that is clearly forced. I find my way back to the narrow streets with brick buildings shouldering in and panes of glass emitting warm, yellow light.

“The Stranger’s Path exists in one form or another in every large community … preserved and cherished. Everywhere it is the direct product of our economic and social evolution. If we seek to dam or bury this ancient river, we will live to regret it.”